MOA Showcases Northwest Coast Art In A Different Light

The Museum of Anthropology (MOA) has recently unveiled a stunning new display space, the Gallery of Northwest Coast Masterworks.

The first exhibition to be housed there is titled In a Different Light: Reflecting on Northwest Coast Art and brings together 110 historical Indigenous artworks, exploring questions of community, culture, and the intricacies of history.

In a Different Light runs at MOA (at UBC, 6393 N.W. Marine Drive) until Spring 2019 and is a product of the curatorial work of Karen Duffek, Jordan Wilson, and Bill McLennan.

The 110 art pieces are found in an intimate 210-square-metre gallery space that will be devoted to Indigenous art from the Northwest Coast. Simply put, it’s gorgeous, melding hyper modern display cases, multimedia elements, and lighting with the natural setting outdoors. The overall effect is intended to be much more of an organic, evolving visitor experience versus the linearity and stasis of some gallery exhibitions.

Visitors will be especially struck by the use of light, some coming naturally from a north-facing window and other light coming from softbox lighting that adjusts its intensity and temperature based on its readings of the sky outside.

The display cases, which are moveable for gallery staff, have been arranged for this exhibition into thematic groups that prompt the visitor to look at Northwest Coast Art differently. Indigenous art has a history of works, through colonization and appropriation, being taken and held in private collections. More recently, First Nations communities have been reclaiming these lost works and their histories and stories.

Together, they showcase the richness and diversity of the artists and their production. Individually, they each tell a different story of the history and active culture of Northwest Coast Indigenous peoples, especially in relation to the land and its resources. In a Different Light celebrates the vitality and “in motion” aspects of these artistic creations.

The range of items is impressive, including blankets, rattles, bowls, woven baskets, carved masks, and clothing. Items are accompanied by descriptions that encourage visitors to think deeply about these pieces thematically and historically. Quotes from artists, curators, and Indigenous community members facilitate conversations about the items as well.

For example, a woven blanket, which belonged to Chief Johnny Xwəyxwayələq of the Musqueam Coast Salish, invites “Witnessing” the spiritual, ceremonial, and class significance of such blankets, as well as Chief Johnny’s testimony at the 1913 McKenna-McBride Royal Commission that removed valuable land from the reserve and replaced it with less valuable land.

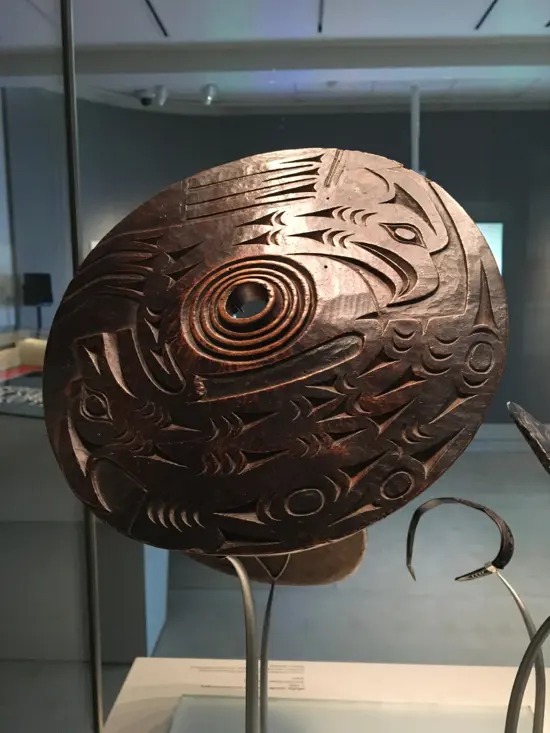

Other art works, like a striking spindle wheel, are about “transforming” everyday utilitarian objects into abstract creations that tell both old and new stories.

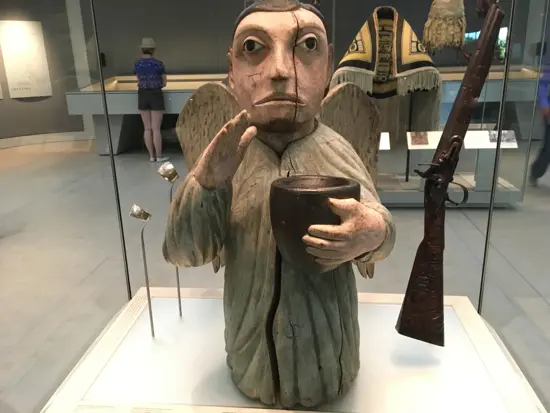

The exhibition also examines the resilience and creativity of Northwest Coast artists in the face of colonization, attempted assimilation, and conflict. An 1886 carved wooden angel from a baptismal font, attributed to Frederick Alexcee, Tsimshian (Lax Kw’alaams), for instance, evidences this meeting of nations and cultures.

A particularly “revealing” work are mid-1800s cedar planks from a painted façade collected in Lax Kw’alaams, a northern coast village of BC. Traditionally, these paintings depicted family crests and animal/spiritual figures in order to display wealth and status. At first glance, the planks look ordinary, but visitors can activate light that reveals some of the original design. The result is breathtaking.

In addition, the exhibition contains multimedia elements, such as film projections and high-tech Idea Chairs, where visitors can listen to the stories of Clyde Tallio (a Nuxalk knowledge keeper, ceremonialist and speaker), Molly Billows (a Homalco Nation spoken-word poet), Rena Point Bolton (a Stó:lō matriarch and artist), and Sharon Fortney (a Coast Salish curator).

Overall, this exciting exhibition brings together the new and the old, the past and the present, and the artistic and the cultural. It’s a fitting inauguration of the MOA’s new gallery space.

Craving

retail

or

nightlife?